An Interview with Tom Lin

By Aditya Gandhi (PO ’22)

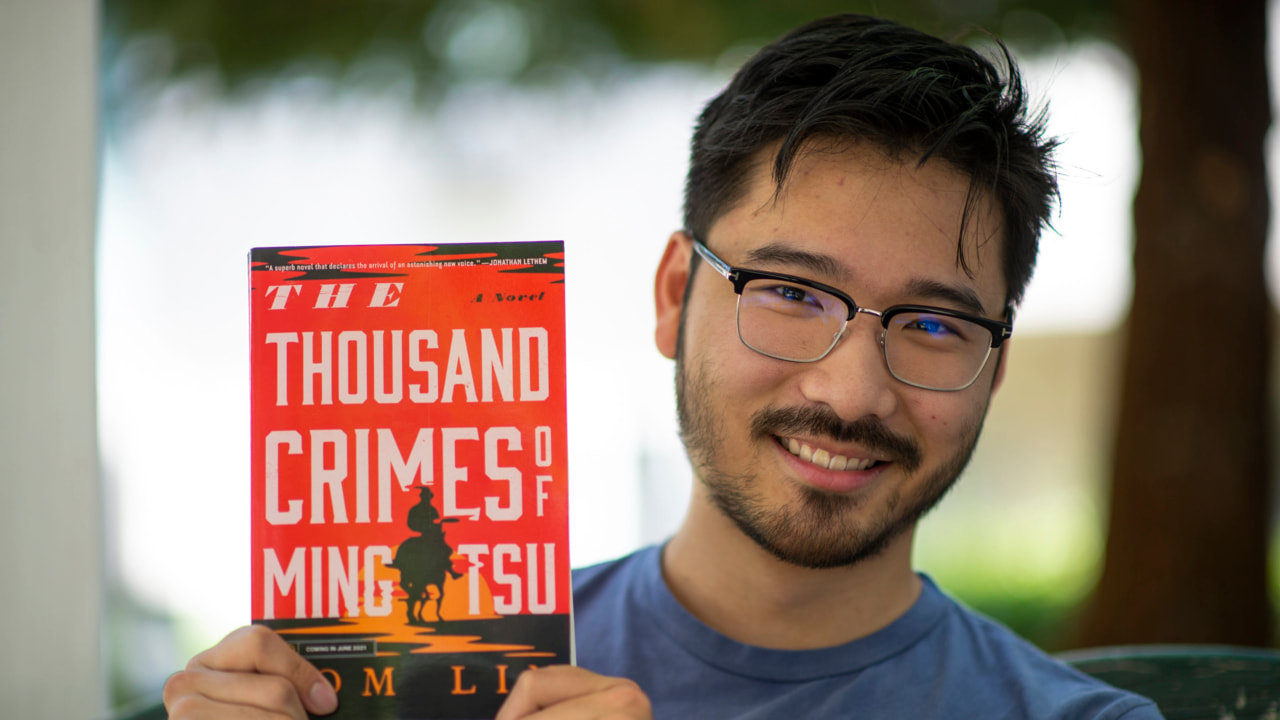

Having immigrated to the United States from China at the age of four, Tom Lin attended Pomona College, where he graduated in 2018. His debut novel, The Thousand Crimes of Ming Tsu, was published in June 2021 and takes the form of a Western centered around a Chinese American outlaw. Lin is currently pursuing a doctorate in Literature at the University of California, Davis.

How did your time at Pomona influence your writing or your relationship with literature?

Pomona was the first time that I had really been on the west coast. I had been taken on a trip by my parents to the American Southwest and Disney—we did Disney and all those places—but that was one week and I was four. So I don't really remember it very well.

I was encountering all these new things, including this landscape, and I just fell in love with it. It really has influenced the way that I think about nature and the world.

Plus, I made a lot of really good friends there. It's always good to have people that you can bounce ideas off of and try new things with.

Speaking of California, it’s such a heavy symbol in American literature, and it’s the primary setting in The Thousand Crimes of Ming Tsu. How do you approach writing about California?

You're right. It's a really laden subject. No, I don't think anyone is really able to write about all of California. I think you pick a section and you try to do it.

I wanted to get California right, or at least whatever tiny part of California I could access, and I really wanted to get the landscape right. The history, all that stuff. So I did a lot of research as I was thinking about it. And that helped me with the way that I ended up approaching this. The more that I knew about California, the easier it was to envision a story that could stick around those facts, rather than trying to invent a story out of whole cloth while also trying to nail the feeling of being in California.

I don't think I could have wrote this book if I hadn't lived in Southern California for four years.

What made you interested in writing a Western?

I haven't really read a lot of Westerns. I mean, I've watched a couple of Westerns, but the Westerns that I've read are mostly meta westerns—examples of the genre about the genre, like Cormac McCarthy or that sort of thing. But I actually don't have a lot of experience with non-ironic, totally sincere classic Westerns. And I think it's interesting to write something that aims at that core while only reading around it or about it.

The other thing about this journey to the genre is that it's such an American genre—it's really conceived in and because of the American West specifically. For most of its history, the Western has been a way of telling a normative history of the United States. The West was won, so to speak, but also why did the West ought to have been won by the people who won it?

It's easy to take a cynical stance to the Western and discard it, but I think it's a really powerful, really potent machine that has an incredible mechanism contained within it. The Western is able to legitimate stories of American sovereignty by nature of the genre. And it's always been used. That machine has always been used for the purpose of legitimating white male supremacy in the American West. But I think it was so much more interesting for me to go in there and see if I could turn the machine around—if I could use this mechanism to try to legitimate a different kind of American while still operating within the bounds of that genre.

Even as you were rewriting the genre from an Asian-American perspective, is there any aspect of the traditional Western that you found yourself wanting to preserve or stay true to?

I guess I think the thing that the genre does that is absolutely critical to it is this ideal that all Westerns espouse, which is that it is good to be maximally present in a time, in a place, in an activity. There's a critic Jane Tompkins who has this book West of Everything. And that's one of the things that she says, that the Western celebrates a moment of being 100% alive at a place, doing a thing at a time. And I always thought that was just totally incredible.

I think the way that the Western uses that to treat the landscape or questions of time and labor and even violence—I think those were aspects of the Western that I felt were worth saving and worth reproducing.

At the same time, it has to grapple with the people that lived there that were expelled. It’s a genre full of contradictions. And I think a lot of those contradictions can be resolved by just ignoring them. Like the Native American raiding parties or violence against women—all of those things aren't part of the Western. The only thing that really is part of the Western as a genre is the respect for total activity and a respect for landscape. I wanted to really carry those two things through.

What are your favorite parts of the writing process?

My favorite part of writing a novel is everything except writing. I think writing is so insanely difficult. Proust has this great line, I think it's in Swann’s Way, where he sees two church steeples. He's remembering, he's riding in a car, and he sees two church steeples and he feels like he has to write something. And so he goes home and almost in a delirium, he puts down a couple words on paper about the church steeples. And then the phrase that he said is, I felt as though I had laid an egg. I've always really agreed with that. Because I think the best part about writing for me is when you've just finished it because you don't have to do it again.

For me, I like to do research, and I like to plan and think about characters. I like to write things that don't actually end up in the text of the novels, like character sketches. I take the most joy in assembly and polish. The thing I find most challenging is invention.

Do you ever feel sad about the character sketches and other little things from your research that don't make it into the novel?

Everything I ever have written is in an X file somewhere on my computer. I'll write down phrases that I think are really cool, and phrases or fragments from those things will make it into the book.

But I think there's too much pressure when I sit down and I'm going to work on the manuscript. So that actually chokes my ability to write anything. When I switched to the lower-stakes act of doing a little character sketch or writing about a location—when I switched gears, I was actually finding that I wrote more and that I felt less inhibited because it was lower stakes.

You're a PhD student at UC Davis, with research interests in science, technology, and speculative fiction. Did those interests factor at all into your writing of The Thousand Crimes of Ming Tsu, or do they factor generally into your writing?

The things that are transferable are the research skills or thinking through a problem or writing as a process—I think those are things that I carry. That approach of using writing to solve problems or issues or to think about mysteries, I think that is something that for me ties together my academic and creative practices.

As far as the subject matter itself, those are kept very distinct in my mind. Much of The Thousand Crimes of Ming Tsu was researched and written before I began specializing in graduate school. But I think it will be interesting because my next project is science-fiction. I think that is going to be interesting when I end up writing something about a topic that I'm also studying.

What specifically do you have in mind for your next project?

I’m only pre-writing right now, which means no writing, just planning and collecting things. I like to think of writing as working with a question. So I think for this next project, the question I'm thinking about is the experience of death. For The Thousand Crimes of Ming Tsu, the question was what does it mean to remember? And I think this next one is what does it mean to die? So light stuff coming from me in the future.

What advice do you have for other writers?

I think my advice is to finish. Whatever you're working on, finish it. And then when you're done, you'll want to start a new thing. And so you just start a new thing and then you should finish that as well.

I had to get a lot of practice with endings because I would always move on to another idea that was more exciting. You end up with very finely developed sense of beginnings and middles, and then when it comes to the ending…yeah.

I think the other piece of advice I would give, and this applies extra for marginalized writers or writers of color, is that you should write about what is familiar to you, and what you know. You should write about yourself.

When I was a kid and I was writing stuff, a lot of times I would just write about a white main character. Not because I thought it would be better, but I’d just never seen a book without a white main character. In my mind, there were two kinds of stories you told. One was you with your friends, and another was this story that would show up in books which just had to have a white person in it. When I first discovered that I didn't have to do that, I remember being like, oh my God, the horizon of what I can write about is suddenly so broad and so much more interesting.

We're also at a great moment right now in publishing where we are seeing a little more representation of those marginalized voices and those marginalized experiences. And just because they’re marginalized doesn't mean they're marginal people. Human stories are what's interesting. And if you can produce a human story, that's cool.

What is the hardest part about writing about yourself?

I think for me the hardest part about writing about myself or using myself as as a source is that you discover answers while you're writing or you discover shapes or patterns. And I think the uncomfortable thing is to pull just a detail out cleanly from yourself or your own experience. As you've been working at it, you find that you've actually pulled all these strings attached to that detail. Like it has all this kind of stuff that has come off with it as you've lifted the detail. And now you have to integrate not only the detail itself, but also all the affordances of that detail and the context of that detail you end up having to build out. Oftentimes you find that you have to include more of yourself than you wanted to at the start. I think that discomfort is something you just have to get used to.

Pomona was the first time that I had really been on the west coast. I had been taken on a trip by my parents to the American Southwest and Disney—we did Disney and all those places—but that was one week and I was four. So I don't really remember it very well.

I was encountering all these new things, including this landscape, and I just fell in love with it. It really has influenced the way that I think about nature and the world.

Plus, I made a lot of really good friends there. It's always good to have people that you can bounce ideas off of and try new things with.

Speaking of California, it’s such a heavy symbol in American literature, and it’s the primary setting in The Thousand Crimes of Ming Tsu. How do you approach writing about California?

You're right. It's a really laden subject. No, I don't think anyone is really able to write about all of California. I think you pick a section and you try to do it.

I wanted to get California right, or at least whatever tiny part of California I could access, and I really wanted to get the landscape right. The history, all that stuff. So I did a lot of research as I was thinking about it. And that helped me with the way that I ended up approaching this. The more that I knew about California, the easier it was to envision a story that could stick around those facts, rather than trying to invent a story out of whole cloth while also trying to nail the feeling of being in California.

I don't think I could have wrote this book if I hadn't lived in Southern California for four years.

What made you interested in writing a Western?

I haven't really read a lot of Westerns. I mean, I've watched a couple of Westerns, but the Westerns that I've read are mostly meta westerns—examples of the genre about the genre, like Cormac McCarthy or that sort of thing. But I actually don't have a lot of experience with non-ironic, totally sincere classic Westerns. And I think it's interesting to write something that aims at that core while only reading around it or about it.

The other thing about this journey to the genre is that it's such an American genre—it's really conceived in and because of the American West specifically. For most of its history, the Western has been a way of telling a normative history of the United States. The West was won, so to speak, but also why did the West ought to have been won by the people who won it?

It's easy to take a cynical stance to the Western and discard it, but I think it's a really powerful, really potent machine that has an incredible mechanism contained within it. The Western is able to legitimate stories of American sovereignty by nature of the genre. And it's always been used. That machine has always been used for the purpose of legitimating white male supremacy in the American West. But I think it was so much more interesting for me to go in there and see if I could turn the machine around—if I could use this mechanism to try to legitimate a different kind of American while still operating within the bounds of that genre.

Even as you were rewriting the genre from an Asian-American perspective, is there any aspect of the traditional Western that you found yourself wanting to preserve or stay true to?

I guess I think the thing that the genre does that is absolutely critical to it is this ideal that all Westerns espouse, which is that it is good to be maximally present in a time, in a place, in an activity. There's a critic Jane Tompkins who has this book West of Everything. And that's one of the things that she says, that the Western celebrates a moment of being 100% alive at a place, doing a thing at a time. And I always thought that was just totally incredible.

I think the way that the Western uses that to treat the landscape or questions of time and labor and even violence—I think those were aspects of the Western that I felt were worth saving and worth reproducing.

At the same time, it has to grapple with the people that lived there that were expelled. It’s a genre full of contradictions. And I think a lot of those contradictions can be resolved by just ignoring them. Like the Native American raiding parties or violence against women—all of those things aren't part of the Western. The only thing that really is part of the Western as a genre is the respect for total activity and a respect for landscape. I wanted to really carry those two things through.

What are your favorite parts of the writing process?

My favorite part of writing a novel is everything except writing. I think writing is so insanely difficult. Proust has this great line, I think it's in Swann’s Way, where he sees two church steeples. He's remembering, he's riding in a car, and he sees two church steeples and he feels like he has to write something. And so he goes home and almost in a delirium, he puts down a couple words on paper about the church steeples. And then the phrase that he said is, I felt as though I had laid an egg. I've always really agreed with that. Because I think the best part about writing for me is when you've just finished it because you don't have to do it again.

For me, I like to do research, and I like to plan and think about characters. I like to write things that don't actually end up in the text of the novels, like character sketches. I take the most joy in assembly and polish. The thing I find most challenging is invention.

Do you ever feel sad about the character sketches and other little things from your research that don't make it into the novel?

Everything I ever have written is in an X file somewhere on my computer. I'll write down phrases that I think are really cool, and phrases or fragments from those things will make it into the book.

But I think there's too much pressure when I sit down and I'm going to work on the manuscript. So that actually chokes my ability to write anything. When I switched to the lower-stakes act of doing a little character sketch or writing about a location—when I switched gears, I was actually finding that I wrote more and that I felt less inhibited because it was lower stakes.

You're a PhD student at UC Davis, with research interests in science, technology, and speculative fiction. Did those interests factor at all into your writing of The Thousand Crimes of Ming Tsu, or do they factor generally into your writing?

The things that are transferable are the research skills or thinking through a problem or writing as a process—I think those are things that I carry. That approach of using writing to solve problems or issues or to think about mysteries, I think that is something that for me ties together my academic and creative practices.

As far as the subject matter itself, those are kept very distinct in my mind. Much of The Thousand Crimes of Ming Tsu was researched and written before I began specializing in graduate school. But I think it will be interesting because my next project is science-fiction. I think that is going to be interesting when I end up writing something about a topic that I'm also studying.

What specifically do you have in mind for your next project?

I’m only pre-writing right now, which means no writing, just planning and collecting things. I like to think of writing as working with a question. So I think for this next project, the question I'm thinking about is the experience of death. For The Thousand Crimes of Ming Tsu, the question was what does it mean to remember? And I think this next one is what does it mean to die? So light stuff coming from me in the future.

What advice do you have for other writers?

I think my advice is to finish. Whatever you're working on, finish it. And then when you're done, you'll want to start a new thing. And so you just start a new thing and then you should finish that as well.

I had to get a lot of practice with endings because I would always move on to another idea that was more exciting. You end up with very finely developed sense of beginnings and middles, and then when it comes to the ending…yeah.

I think the other piece of advice I would give, and this applies extra for marginalized writers or writers of color, is that you should write about what is familiar to you, and what you know. You should write about yourself.

When I was a kid and I was writing stuff, a lot of times I would just write about a white main character. Not because I thought it would be better, but I’d just never seen a book without a white main character. In my mind, there were two kinds of stories you told. One was you with your friends, and another was this story that would show up in books which just had to have a white person in it. When I first discovered that I didn't have to do that, I remember being like, oh my God, the horizon of what I can write about is suddenly so broad and so much more interesting.

We're also at a great moment right now in publishing where we are seeing a little more representation of those marginalized voices and those marginalized experiences. And just because they’re marginalized doesn't mean they're marginal people. Human stories are what's interesting. And if you can produce a human story, that's cool.

What is the hardest part about writing about yourself?

I think for me the hardest part about writing about myself or using myself as as a source is that you discover answers while you're writing or you discover shapes or patterns. And I think the uncomfortable thing is to pull just a detail out cleanly from yourself or your own experience. As you've been working at it, you find that you've actually pulled all these strings attached to that detail. Like it has all this kind of stuff that has come off with it as you've lifted the detail. And now you have to integrate not only the detail itself, but also all the affordances of that detail and the context of that detail you end up having to build out. Oftentimes you find that you have to include more of yourself than you wanted to at the start. I think that discomfort is something you just have to get used to.