Yi Yi: Retrospective Truths

Alan Ke

To my knowledge, most kids don’t spend their seventh birthdays 35,000 feet above the Pacific Ocean. If it were up to me, I’d have chosen to celebrate somewhere like Chuck E. Cheese’s, anywhere other than the 13-hour purgatory of EWR to PEK. On a whim, we packed our bags as a family, swapping the comfort of a small suburban town in New Jersey for the monolithic metropolis of Beijing.

At first, every bone in my body teamed together to reject the Chinese culture imposed onto my (so-called) American upbringing. In public, I’d assert my American-ness by speaking exclusively in English. At home, I abstained from any television besides the Chinese-dubbed runs of Lilo & Stitch. However much I tried, my acts of stubbornness proved no match to the indifferent rhythms of city life. To me, Beijing wasn’t just foreign or impersonal, it was isolating. It was a city I thought I’d never call home.

Since its premiere in 2000, Edward Yang’s Yi Yi has commonly been credited as a film about everything. Its expansive scope and thematic breadth mean that every viewer is bound to latch onto something different about the film. For me, the film stands for a poignant image of East Asian urban life almost unrecognizable today. Growing up in China for over a decade, I learned to overcome my internalized biases as well as appreciate the vibrance of life in its capital. Though it’s set in Taiwan, watching Yi Yi for the first time reminded me of the city 6,000 miles away from California that I now consider home, a place I had once unfairly written off. A relic of a bygone era, Yang’s final film effortlessly captures the energies of Taiwan before the shadows of modernity and westernization took over the east by storm.

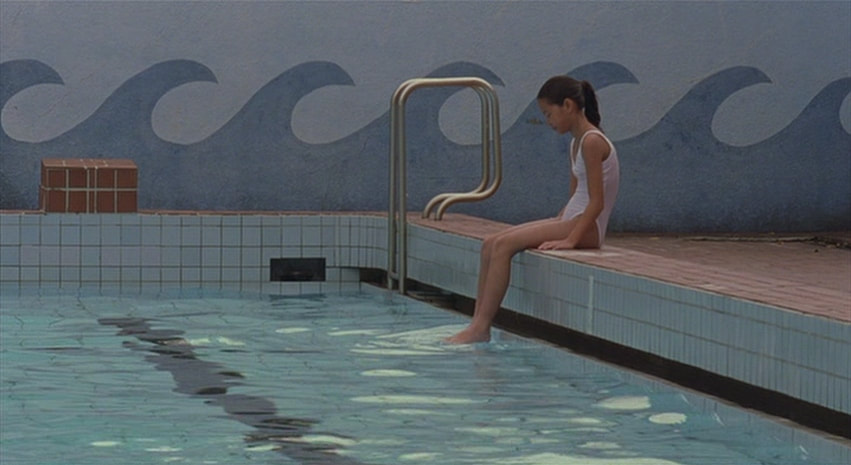

The film opens with the formalities of a wedding celebration, the first of three family gatherings that loosely structure the story. We follow the Jians, a middle-class family living in Taipei City, as they make their way to the reception. NJ (whose name I can’t help but associate with my home state of New Jersey), brother of the groom and father of the Jian household, runs into Sherry, who we later learn to be his first romantic interest. Witness to the tense encounter is NJ’s eight-year-old son Yang-Yang, one of the two figures through whom the film explores childlike innocence and youth, the other being his adolescent sister Ting-Ting. Like the selectiveness of our memories, most films view childhood subjectively through the rose-colored lens of nostalgia. Yi Yi instead favors those formative moments that often go by unnoticed, whether cheerful or not.

Upon returning from the wedding, the family learns that Grandma has been hospitalized after suffering a stroke. During this scene, we get the first of Yang’s masterful long takes. NJ and his wife Min-Min rush into the hospital lobby, followed by the drunken groom and his rowdy friends. Instead of focusing directly on their clumsy antics, the sequence plays out through their reflections on the window. With city lights bleeding through the image, we’re reminded of the outside world ignorant of the family’s distress. Yang frequently employs this visual motif, focusing not on the action, but its settings. This lens of objectivity grounds the film’s emotional peaks and troughs in the urban rhythms we take for granted, from the capriciousness of traffic lights to the measured cadence of public transit. The characters in Yi Yi don’t just live in Taipei; they live with it. These synchronicities define the inextricable bond between individual and city, the invisible forces that dictate the overlap and congruities in the metropolitan ecosystems we inhabit.

Though the neon glow that illuminates Edward Yang’s Taipei has all but vanished for the static luminescence of LED displays, the set design makes the film all that more distinctive and pronounced. A handful of shots are shown through the watchful eyes of surveillance cameras but not in a particularly insidious manner, predating the omnipresent hold it has taken in our current lives. Vaguely impressionistic paintings decorate apartment walls, offering refuge from the bustling cities they’re housed in. A tiny New York bagel shop acts as a rendezvous point for Ting-Ting’s dates—a precursor to the wave of western coffee shops and bakeries that overtook the streets of so many cities. The sets capture every last detail, down to the innocuous placement of Dutch butter cookie tins repurposed into storage boxes I’d so often see on my own visits to my grandparents. All these minor aspects add up to evoke a near-perfect image of Taiwan at the turn of the 21st century, right at the cusp of becoming the booming metropolis that it is today.

In today’s context, it’s easy to read Yi Yi almost as a period piece, but it’s important to note its forward-thinking tendencies. There’s an uncertainty in the film’s presentation of Taiwan. As a country whose independence has been hard fought, having undergone periods of Japanese occupation and Chinese rule, the bearings of history reverberate through the dialogue. When speaking to Sherry, NJ communicates almost exclusively in Taiwanese, a language with origins in both classical Chinese and Japanese. There’s a poetic elegance to their exchanges, trying to rekindle their former affection with a language rooted in the past.

Taiwan’s complex history with Japan is further muddled by the introduction of Mr. Ota, a Japanese business partner whom NJ befriends. However, there’s an air of distrust among NJ’s colleagues, hesitant to risk the company in the hands of a Japanese video game company. Over dinner, Mr. Ota seems to ask not of NJ but Taiwan, “Why are we afraid of the first time? Every day in life is the first time. Every morning is new. We’re never afraid of getting up every morning. Why?”

Much of this weight of uncertainty is placed on the shoulders of the film’s youngest character, Yang-Yang. Instead of fear, the child approaches life with curiosity. In one scene, he asks his father, “Can we only know half of the truth? We can only see what’s in front and not what’s behind.” Taking this into account, the film is seemingly at odds with itself. On one hand, this echoes Yang’s unconventional approaches to cinematography, introducing new ways of viewing familiar images. On the other hand, the frequent use of long takes means that we’re only offered one perspective, often shown the expressions of one character but not the other. This begs the question: can we ever know any truth other than our own? If so, can it be made known through film? Yi Yi is a film that asks more questions than it can ever answer. That, in part, is its brilliance.

Perhaps the truth Yang-Yang seeks is not one that’s offered by the perspective of another, but rather by the perspective accumulated with time. The film illustrates this concept through retrospective proximity, suggesting our memories of events aren’t dictated by our experiences so much as our distance from them. Yi Yi intricately weaves each thread in the multigenerational Jian household into an elaborate tapestry. Seemingly inconsequential actions have repercussions that reverberate across the narrative. NJ’s aftertaste of first love echoes the budding romance Ting-Ting experiences, which in turn expounds upon the hints of attraction felt by Yang-Yang. Individually, they’re all vignettes of endearing moments at different stages of life. Taken together, they form a much bigger picture. Life isn’t experienced just through memories; it’s the spaces between them that constitute our truths.

As it turns out, Yang-Yang was right. The short-sightedness of our perception can never capture the whole truth, the same way it took me so long to recognize the place I call home. For me, the film is a reminder of many things: family, city life, tradition, childhood. But Yi Yi isn’t about any of those one subjects; it’s about them all. It’s about life.

Alan (Pomona '23) makes music under the moniker Dustbreather and is looking to form a band.

At first, every bone in my body teamed together to reject the Chinese culture imposed onto my (so-called) American upbringing. In public, I’d assert my American-ness by speaking exclusively in English. At home, I abstained from any television besides the Chinese-dubbed runs of Lilo & Stitch. However much I tried, my acts of stubbornness proved no match to the indifferent rhythms of city life. To me, Beijing wasn’t just foreign or impersonal, it was isolating. It was a city I thought I’d never call home.

Since its premiere in 2000, Edward Yang’s Yi Yi has commonly been credited as a film about everything. Its expansive scope and thematic breadth mean that every viewer is bound to latch onto something different about the film. For me, the film stands for a poignant image of East Asian urban life almost unrecognizable today. Growing up in China for over a decade, I learned to overcome my internalized biases as well as appreciate the vibrance of life in its capital. Though it’s set in Taiwan, watching Yi Yi for the first time reminded me of the city 6,000 miles away from California that I now consider home, a place I had once unfairly written off. A relic of a bygone era, Yang’s final film effortlessly captures the energies of Taiwan before the shadows of modernity and westernization took over the east by storm.

The film opens with the formalities of a wedding celebration, the first of three family gatherings that loosely structure the story. We follow the Jians, a middle-class family living in Taipei City, as they make their way to the reception. NJ (whose name I can’t help but associate with my home state of New Jersey), brother of the groom and father of the Jian household, runs into Sherry, who we later learn to be his first romantic interest. Witness to the tense encounter is NJ’s eight-year-old son Yang-Yang, one of the two figures through whom the film explores childlike innocence and youth, the other being his adolescent sister Ting-Ting. Like the selectiveness of our memories, most films view childhood subjectively through the rose-colored lens of nostalgia. Yi Yi instead favors those formative moments that often go by unnoticed, whether cheerful or not.

Upon returning from the wedding, the family learns that Grandma has been hospitalized after suffering a stroke. During this scene, we get the first of Yang’s masterful long takes. NJ and his wife Min-Min rush into the hospital lobby, followed by the drunken groom and his rowdy friends. Instead of focusing directly on their clumsy antics, the sequence plays out through their reflections on the window. With city lights bleeding through the image, we’re reminded of the outside world ignorant of the family’s distress. Yang frequently employs this visual motif, focusing not on the action, but its settings. This lens of objectivity grounds the film’s emotional peaks and troughs in the urban rhythms we take for granted, from the capriciousness of traffic lights to the measured cadence of public transit. The characters in Yi Yi don’t just live in Taipei; they live with it. These synchronicities define the inextricable bond between individual and city, the invisible forces that dictate the overlap and congruities in the metropolitan ecosystems we inhabit.

Though the neon glow that illuminates Edward Yang’s Taipei has all but vanished for the static luminescence of LED displays, the set design makes the film all that more distinctive and pronounced. A handful of shots are shown through the watchful eyes of surveillance cameras but not in a particularly insidious manner, predating the omnipresent hold it has taken in our current lives. Vaguely impressionistic paintings decorate apartment walls, offering refuge from the bustling cities they’re housed in. A tiny New York bagel shop acts as a rendezvous point for Ting-Ting’s dates—a precursor to the wave of western coffee shops and bakeries that overtook the streets of so many cities. The sets capture every last detail, down to the innocuous placement of Dutch butter cookie tins repurposed into storage boxes I’d so often see on my own visits to my grandparents. All these minor aspects add up to evoke a near-perfect image of Taiwan at the turn of the 21st century, right at the cusp of becoming the booming metropolis that it is today.

In today’s context, it’s easy to read Yi Yi almost as a period piece, but it’s important to note its forward-thinking tendencies. There’s an uncertainty in the film’s presentation of Taiwan. As a country whose independence has been hard fought, having undergone periods of Japanese occupation and Chinese rule, the bearings of history reverberate through the dialogue. When speaking to Sherry, NJ communicates almost exclusively in Taiwanese, a language with origins in both classical Chinese and Japanese. There’s a poetic elegance to their exchanges, trying to rekindle their former affection with a language rooted in the past.

Taiwan’s complex history with Japan is further muddled by the introduction of Mr. Ota, a Japanese business partner whom NJ befriends. However, there’s an air of distrust among NJ’s colleagues, hesitant to risk the company in the hands of a Japanese video game company. Over dinner, Mr. Ota seems to ask not of NJ but Taiwan, “Why are we afraid of the first time? Every day in life is the first time. Every morning is new. We’re never afraid of getting up every morning. Why?”

Much of this weight of uncertainty is placed on the shoulders of the film’s youngest character, Yang-Yang. Instead of fear, the child approaches life with curiosity. In one scene, he asks his father, “Can we only know half of the truth? We can only see what’s in front and not what’s behind.” Taking this into account, the film is seemingly at odds with itself. On one hand, this echoes Yang’s unconventional approaches to cinematography, introducing new ways of viewing familiar images. On the other hand, the frequent use of long takes means that we’re only offered one perspective, often shown the expressions of one character but not the other. This begs the question: can we ever know any truth other than our own? If so, can it be made known through film? Yi Yi is a film that asks more questions than it can ever answer. That, in part, is its brilliance.

Perhaps the truth Yang-Yang seeks is not one that’s offered by the perspective of another, but rather by the perspective accumulated with time. The film illustrates this concept through retrospective proximity, suggesting our memories of events aren’t dictated by our experiences so much as our distance from them. Yi Yi intricately weaves each thread in the multigenerational Jian household into an elaborate tapestry. Seemingly inconsequential actions have repercussions that reverberate across the narrative. NJ’s aftertaste of first love echoes the budding romance Ting-Ting experiences, which in turn expounds upon the hints of attraction felt by Yang-Yang. Individually, they’re all vignettes of endearing moments at different stages of life. Taken together, they form a much bigger picture. Life isn’t experienced just through memories; it’s the spaces between them that constitute our truths.

As it turns out, Yang-Yang was right. The short-sightedness of our perception can never capture the whole truth, the same way it took me so long to recognize the place I call home. For me, the film is a reminder of many things: family, city life, tradition, childhood. But Yi Yi isn’t about any of those one subjects; it’s about them all. It’s about life.

Alan (Pomona '23) makes music under the moniker Dustbreather and is looking to form a band.